RFK Jr.’s New Food Pyramid vs. Old Food Pyramid

Table of Contents

RFK Jr.’s New Food Pyramid vs. Old Food Pyramid

Rethinking What We Were Taught About Food—From an Asian Perspective

I grew up believing that rice was non-negotiable. Breakfast, lunch, dinner—rice was there. If you removed it, the meal felt incomplete, almost irresponsible. This belief didn’t come only from culture; it came from nutrition education, from posters in schools, from doctors who spoke about “energy foods,” and from decades of public health messaging shaped—directly or indirectly—by the old food pyramid.

So when I encountered the discussion around the new food pyramid proposed under the leadership of Robert F. Kennedy Jr., I didn’t just see a policy shift. I felt like something deeply ingrained in me—as a Filipino, as an Asian, as someone raised to fear fat and trust carbohydrates—was being questioned.

This debate matters far beyond the United States. It matters to us.

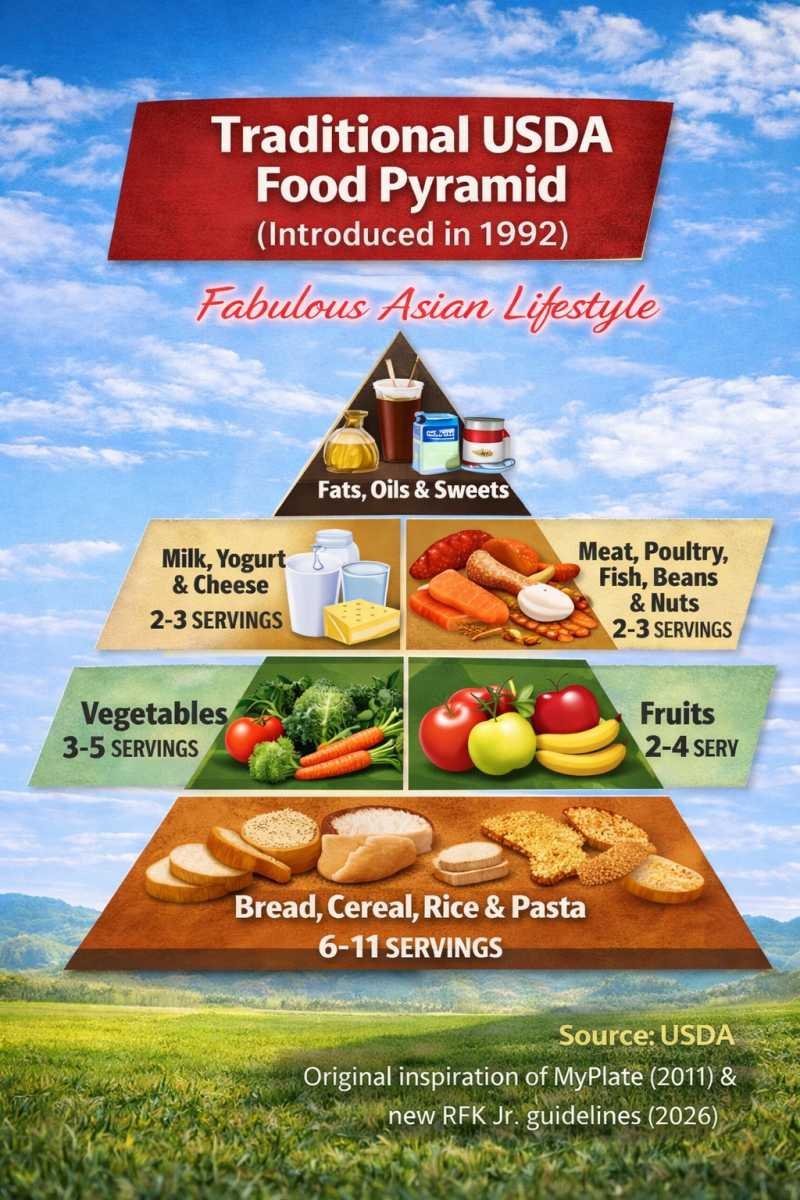

What the Old Food Pyramid Really Taught Us

The original U.S. Food Pyramid, introduced in 1992, placed grains at the base, encouraging 6–11 servings per day. Fat was pushed to the top—something to be minimized. Protein was important, but secondary. This model shaped nutrition education worldwide, including in many Asian countries where carbohydrates were already culturally dominant.

Even when the pyramid was replaced by MyPlate in 2011, the underlying philosophy remained largely the same:

carbohydrates are safe, fat is risky, and balance means moderation—especially of meat and oil.

This historical framework is documented in the USDA’s overview of

A Brief History of USDA Food Guides.

For Asians, this guidance blended seamlessly into existing food traditions. Rice-heavy diets were not questioned; they were validated. The pyramid didn’t challenge our habits—it reinforced them.

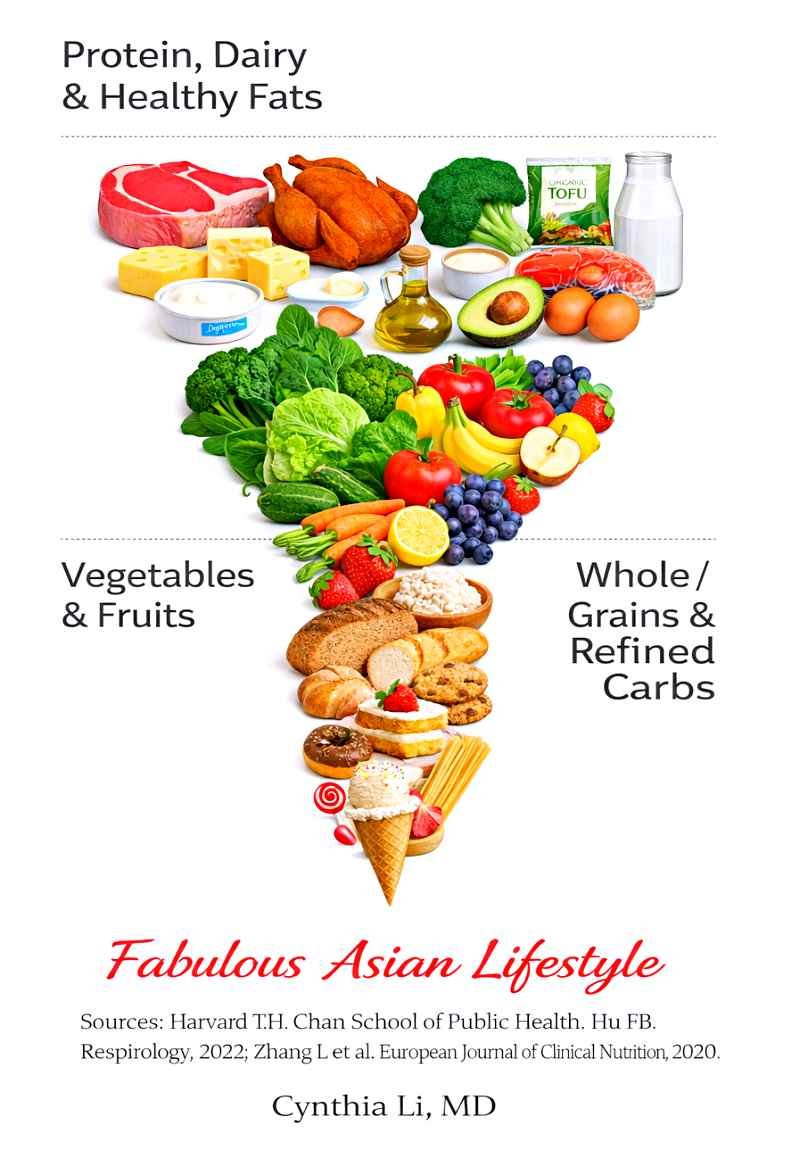

What the NRFK Jr.’s New Food Pyramid Proposes—and Why It’s Controversial

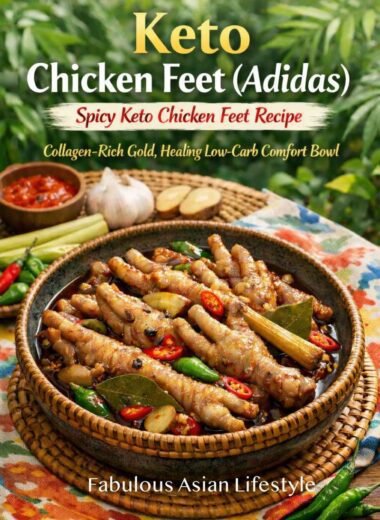

The newly proposed model flips decades of thinking. Instead of carbohydrates forming the base, protein and whole foods are emphasized. Ultra-processed foods and added sugars are strongly discouraged. Natural fats—previously demonized—are reintroduced as acceptable when minimally processed.

The core message is blunt:

Chronic disease is not driven by fat alone, but by processed food and excessive refined carbohydrates.

This shift is outlined in People Magazine’s coverage,

RFK Jr. Unveils an Upside-Down Food Pyramid,

and further analyzed in Live Science’s explainer,

New U.S. food pyramid recommends a very high-protein diet.

This is not just a design change—it’s a philosophical one.

What Is the Advocacy of the RFK Jr.’s New Food Pyramid?

To understand the advocacy behind the new food pyramid, we need to be clear about what it is not.

It is not:

- A call to eat unlimited meat

- A rejection of vegetables

- A permission slip to eat carelessly

Instead, its advocacy can be understood through five core teachings, meant to correct what proponents see as decades of nutritional misunderstanding.

1. Eat Real Food First

At the heart of the new pyramid is the belief that food quality matters more than food categories.

Instead of asking:

“Is this low-fat?”

The new model asks:

“Is this food close to its natural form?”

This means prioritizing:

- Whole cuts of meat instead of processed meats

- Eggs instead of sugary breakfast cereals

- Vegetables that are fresh or minimally cooked

- Fats that come from real sources (butter, olive oil) rather than industrial oils

This principle aligns with findings discussed by Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in

Ultra-processed foods and health.

The advocacy here is anti–ultra-processed food, not anti-carbohydrate or pro-meat at all costs.

2. Protein Is Foundational, Not Optional

The new pyramid places protein at the center because protein:

- Builds and preserves muscle

- Stabilizes blood sugar

- Improves satiety (feeling full longer)

Advocates argue that many modern diets—especially carb-heavy ones—leave people under-proteined but overfed.

This is especially relevant for Asians, who may eat large portions of rice with relatively small amounts of protein.

These effects are well documented in the National Institutes of Health review,

Dietary Protein and Weight Management.

The teaching is not eat more food, but eat more nourishing food.

3. Not All Fats Are the Enemy

One of the strongest advocacies of the new pyramid is the rejection of the idea that all fats are harmful.

Instead, it distinguishes:

- Natural fats (from dairy, meat, plants)

- Versus industrial, highly refined seed oils and trans fats

Large-scale evidence reviews, such as the British Medical Journal’s paper on

Saturated fat and health outcomes,

suggest that naturally occurring fats behave very differently from processed fats in the body.

The pyramid teaches discernment—not indulgence.

4. Carbohydrates Are Not Evil—but They Are Not Neutral

This is perhaps the most misunderstood part.

The new advocacy does not ban carbohydrates. Instead, it teaches that:

- Refined carbohydrates (white rice, sugar, white flour) raise blood sugar quickly

- Frequent spikes strain insulin regulation over time

For populations already genetically predisposed to diabetes—such as many Asian groups—this matters deeply.

Harvard’s explanation of

Carbohydrates and Blood Sugar

helps clarify why moderation—not elimination—is the message.

5. Chronic Disease Is a Systems Problem

Finally, the advocacy behind the new pyramid reframes obesity, diabetes, and heart disease not as failures of willpower—but as outcomes of food systems, policy, and education.

This shifts health away from moral judgment and toward structural responsibility.

What Does Science Say? Is This Shift Valid? [ RFK Jr.’s New Food Pyramid ]

This is where the conversation becomes uncomfortable—but necessary.

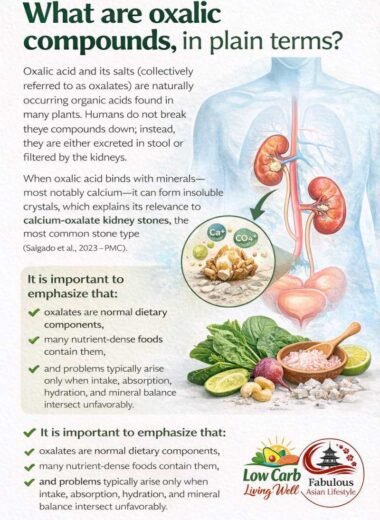

Research increasingly links excess refined carbohydrates to insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes, particularly in Asian populations who develop these conditions at lower body weights.

(See Harvard’s overview on

carbohydrates and metabolic health.)

Higher protein intake has been consistently associated with improved appetite control and blood sugar stability

(NIH review).

Large evidence reviews also show no consistent link between natural saturated fat intake and heart disease when consumed in whole-food contexts

(BMJ analysis).

So yes—there is scientific grounding, even if consensus is still evolving.

So Were Our Previous Beliefs Wrong?

Not wrong—incomplete.

They reflected:

- The science available at the time

- Political and industrial constraints

- The need for simple public messaging

What failed was nuance.

Implications of RFK Jr.’s New Food Pyramid for Asians

Asians are more metabolically sensitive to high-carbohydrate diets and tend to develop diabetes earlier.

This reality is outlined by the World Health Organization in

Diabetes and Asian populations.

Dietary guidance that ignores this sensitivity may unintentionally cause harm.

What This RFK Jr.’s New Food Pyramid Means for the Next Generation

Future generations may inherit:

- More flexible nutrition education

- Greater emphasis on critical thinking

- Less dogma, more evidence

Final Reflection

I do not see the new food pyramid as a commandment. I see it as an invitation to think again.

For Asians, the challenge is not abandoning tradition—but protecting it from modern excess.

Nutrition should honor culture—but never at the expense of health.

References

- A Brief History of USDA Food Guides – USDA

- RFK Jr. Unveils Upside-Down Food Pyramid – People Magazine

- New U.S. Food Pyramid Analysis – Live Science

- Carbohydrates and Blood Sugar – Harvard T.H. Chan

- Dietary Protein and Weight Management – NIH

- Saturated Fat and Health Outcomes – BMJ

- Diabetes – World Health Organization

RFK Jr.’s New Food Pyramid vs. Old Food Pyramid

More Stories