Table of Contents

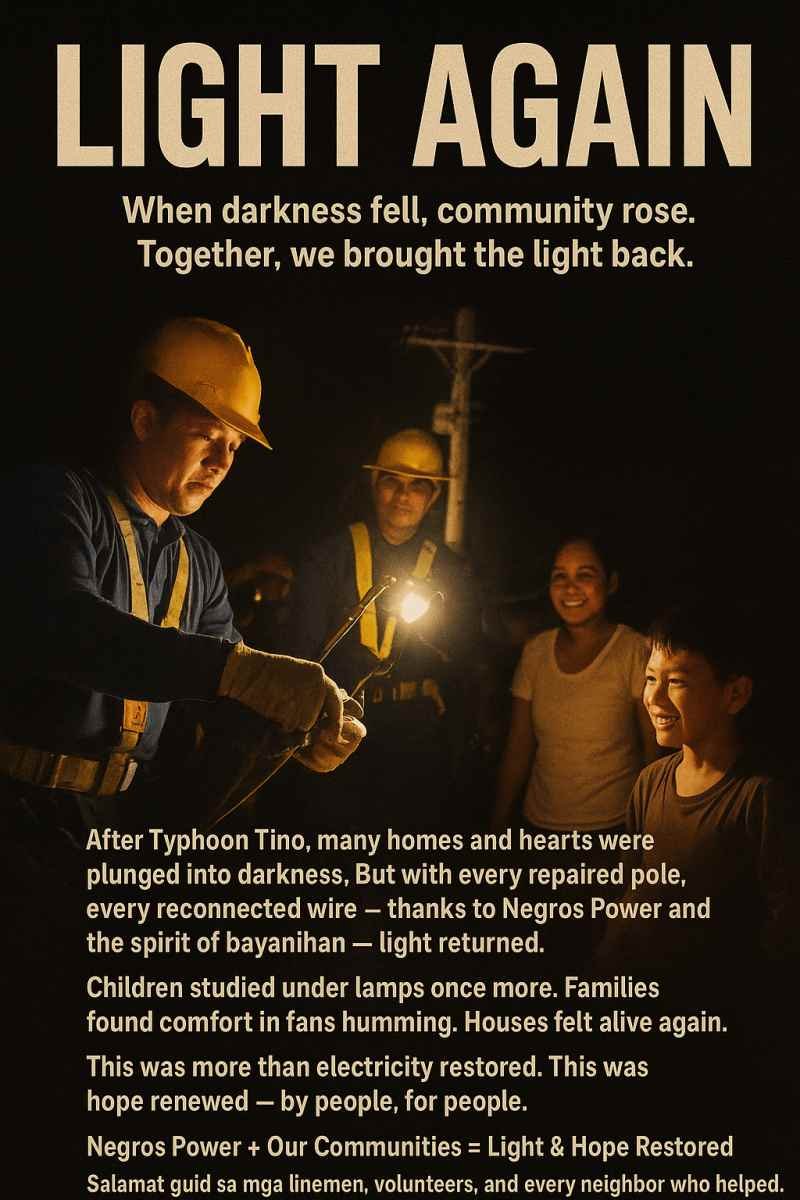

After the Darkness: How Negros Power and the Spirit of Bayanihan Lit Up Negros Again

Ako mismo naka-agom sang pagkadulom sang Typhoon Tino. When the storm barreled through on November 4, 2025, it felt like somebody suddenly pulled the plug on our entire community. Lights blinked out, appliances died mid-use, and the familiar hum of the city disappeared. For days, the nights were heavier—literal kag emosyonal.

But a few weeks later, when electricity finally returned, it didn’t feel like a simple switch flipped back on. It felt like a community rising together.

Why Power Restoration Hit Home — For Me and For Everyone

Losing electricity wasn’t just about losing light. My refrigerator’s contents slowly warmed, fans that kept us comfortable during humid nights stopped turning, and online work halted. My students messaged me—when they could—saying they couldn’t charge their phones to attend classes.

Families with small children struggled. Homes with elderly members had to improvise ways to keep medication cool or maintain safety in the dark. I saw my neighbors queuing anywhere they could find an active outlet. Others fetched water earlier than usual. Even basic routines felt like challenges.

No wonder when electricity finally returned, many of us breathed the same sigh of relief. Light meant normal life inching back.

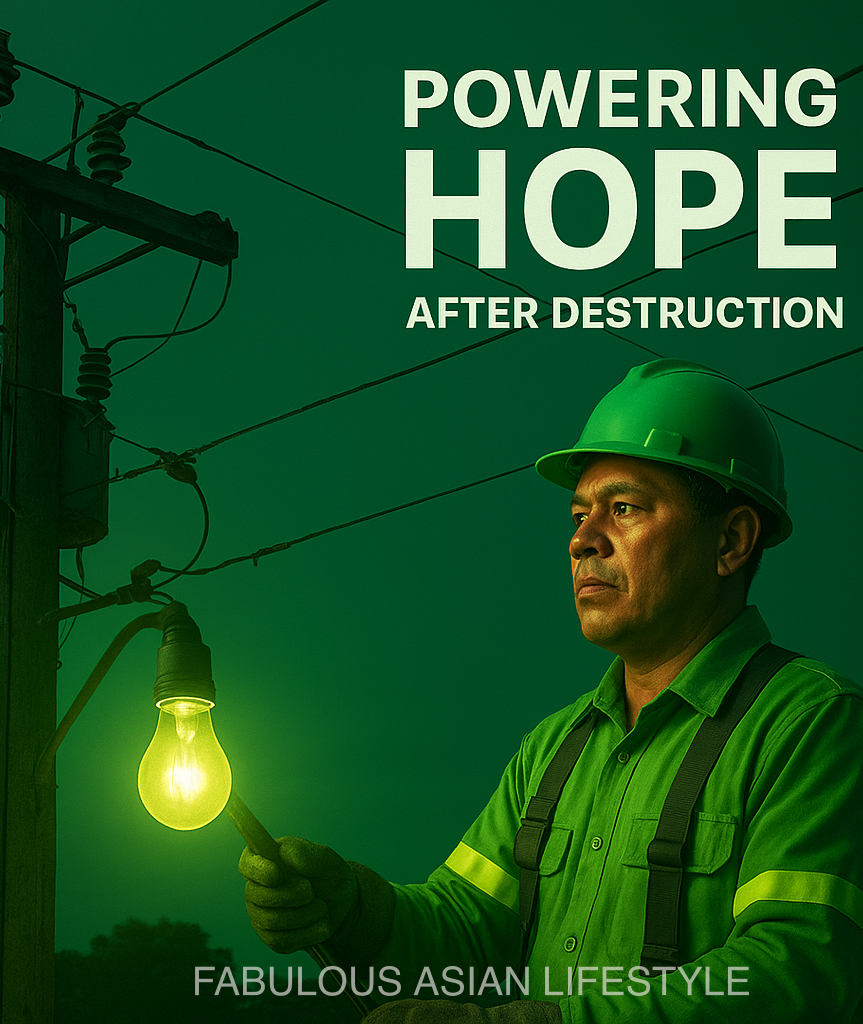

Teamwork Behind the Quick Turnaround

DOE Undersecretary Sharon Garin highlighted something important: it wasn’t just equipment or trucks that made the restoration possible—it was people. She pointed out how Negros Power field crews worked relentlessly, and how barangays and residents supported clearing and access.

Different reports showed massive progress in a short time. Main infrastructures—sub-transmission lines, substations, and feeders—were restored ahead of schedule. Bacolod City, with more than 157,000 customers, saw almost its entire secondary network energized quickly, leaving only a tiny percentage waiting for final fixes.

Across Negros Power’s coverage area, a remarkable majority—over 95%—were reconnected not long after the storm. Considering how widespread the damage was, the pace surprised even long-time residents.

What Made It Difficult — And How Crews Pushed Through

Restoring power isn’t simply plugging wires back together. Many places were hard to reach. Some sitios needed manual pole-carrying because vehicles couldn’t enter. A number of homes had damaged service entrances, making reconnection unsafe. Other areas had privately owned poles or transformers that required clearance before crews could proceed.

Despite all that, the linemen stayed on the ground—day, night, even early dawn—doing whatever they could. I personally saw a team working past 9 p.m. near our street, mud up to their ankles but still pushing to finish reconnecting the line.

Their dedication felt personal. It wasn’t just service—it was solidarity.

Beyond Wires — A Proof of What Community Can Do

What touched me the most was how bayanihan surfaced again in Negros. People helped clear fallen branches, barangay tanods guided work crews, neighbors brought food and water to exhausted linemen, and volunteers helped create safe paths in remote areas.

When our electricity finally came back, it wasn’t just a bulb lighting up—it was a sign that Negros was healing.

Fans hummed again. Children could study. Phones could charge. Families could sleep with less worry.

It felt like hope switching back on.

A Promise to Restore What’s Left — And to Improve

Negros Power acknowledged that the last remaining households waiting for connection are in places with severe damage or difficult access. Still, they committed to finishing the job—no matter how far, no matter how tedious.

As someone living in the middle of all this, ako guid ya ka-appreciate. The linemen, the residents, the volunteers, the LGUs—everybody played a role. This experience reminded me that even in the worst moments, we rebuild faster when we carry the weight together.

And in those first moments when the light returned to my house, I realized:

Resilience isn’t just something we talk about here in Negros.

It’s something we live.

More Stories

- Verbena, Trash, Failed Projects — and the Urgent Call for Accountability

- How Central Negros Found Its Power After Typhoon Tino

- Negros Power Disaster Recovery : A Turning Point for Central Negros

- Miss Universe’s Reputation on Trial

- After the Darkness: How Negros Power and the Spirit of Bayanihan Lit Up Negros Again

- Power Restoration Update | Negros Power

- CINDY VALENCIA: A JOURNEY OF HEART, HUMILITY, AND PURPOSE

- 100 Sacks of Rice Donated by Negros Power to Typhoon Victims

- Negros Power Releases November 2025 Rates

- Negros Power Nears Full Restoration After Typhoon Tino

- ASUS ROG Grand Tech Fair 2025: Massive Laptop Deals