Gen X Childhood

Table of Contents

Why I Am Who I Am: Gen X Childhood in the Philippine Countryside

Born 1968 | Sugarfields | Scarcity, Silence, and Self-Reliance

NOTE: This is written as Part 1 of a series, intentionally expansive, reflective, and grounded in lived Philippine history.

I was born in 1968, into a generation that didn’t grow up being explained to—but learned instead by watching, absorbing, and quietly adjusting.

I grew up on a farm. A sugar cane farm.

We were eight in the family, and life in the 1970s was neither romantic nor tragic—it was simply real.

Only later did psychologists give names to the traits we developed. Only later did the world call us Generation X.

What It Means to Be Gen X (Before It Had a Name)

Generation X—those born roughly between 1965 and 1980—is often described as pragmatic, skeptical, independent, resilient, and emotionally contained. These are not personality quirks. They are adaptive responses.

Psychologists note that Gen X traits were shaped by:

- economic instability

- political uncertainty

- early responsibility

- limited adult supervision

- rapid social change

(See: Strauss & Howe, Generations Theory, Psychology Today)

We didn’t grow up being told how to feel.

We grew up learning when to keep going.

Our TV Was “National.” And It Was an Event | Gen X Childhood

Our television was a National brand—a large, heavy, wooden box with a door that opened and locked. It looked more like furniture than a gadget. When it was off, you closed the doors, as if tucking it to sleep.

The sound didn’t come from the TV.

It came from our Radiophono—a turntable.

We had 45 RPM records and long-play albums, stacked, treasured, replayed until the grooves wore thin. Some of those records didn’t even get played anymore—they became wall décor, cultural artifacts before we knew what that meant.

There was no electricity in the farm.

We powered the TV using a car battery.

At night, people from nearby farms would come to our house to watch. It felt like a small cinema—neighbors standing, children sitting on the floor, everyone quiet when the show started.

I didn’t enjoy it.

My assigned task was to scrub the floor, using a coconut husk brush, mud, and water—especially during rainy days when the house seemed determined to collect dirt faster than I could remove it.

That task was horrible.

And formative.

Psychologists link early responsibility without constant praise to the development of self-regulation and internal motivation, traits strongly associated with Gen X adults (Ryan & Deci, Self-Determination Theory).

Water Was Free. And We Thought It Always Would Be | Gen X Childhood

We didn’t have bottled water.

The idea would have sounded absurd.

We drank from a manual water pump, which we called bomba. Water was abundant, clean, and unquestioned.

Fast forward to today, where water can be more expensive than gasoline—and yes, that still sounds ridiculous to me.

That early abundance taught us something subtle but enduring:

- essentials are not brands

- survival doesn’t require packaging

- value is not always priced

Research on generational value systems shows Gen X is consistently less impressed by consumer signaling and more oriented toward function than form (Twenge & Campbell, American Psychological Association).

Sugar, Survival, and the Marcos Sr. Years | Gen X Childhood

Our family thrived in the sugar industry, but the sugar crisis during the Marcos Sr. era was brutal.

Small farmers began drowning in crop loans.

Farm implements became more expensive.

Sugar prices dropped sharply.

Portions of our land were used as collateral with banks.

Some of those loans were never settled—not because farmers refused to pay, but because banks themselves collapsed.

I remember one bank vividly: Rural Bank of the Philippines (RPB) in the downtown area. Today, that building is MO2 Hotel.

We only recovered that collateral many years later, through PNB, and eventually sold it anyway.

Loss, recovery, and release—without ceremony.

These economic pressures were not isolated. They were systemic. And they were one of the unspoken reasons rebellion began to rise during that time. When people lose land, livelihood, and dignity quietly, unrest grows quietly too.

This environment—where systems failed without apology—taught Gen X a lasting lesson:

Never assume institutions will save you.

Sociological research confirms that cohorts exposed to prolonged economic instability tend to develop institutional skepticism and self-reliant coping strategies (APA, developmental stress literature).

Martial Law and the Holes We Dug | Gen X Childhood

I didn’t fully understand Martial Law.

But I remember this clearly:

My father dug holes in our land to bury family firearms.

Military searches were real. Sudden. Unpredictable.

Children didn’t ask questions.

Adults didn’t explain.

They just acted.

This kind of early exposure to controlled fear and normalized uncertainty is known to shape:

- calmness under pressure

- emotional containment

- heightened situational awareness

(See: NIH studies on early environmental stress and adaptive behavior)

That is Gen X emotional architecture in a sentence:

Feel deeply. React selectively. Move quietly.

Food Was Everywhere | Gen X Childhood

Life on the farm was abundant.

Not curated.

Not calculated.

Just… there.

We had:

- free-range chickens (no one stole—everyone had their own)

- ducks laying eggs daily

- goats

- pigs

- rice fields producing upa (rice hulls) and ulon-ulon—partially developed grains used as feed for our poultry

- rows of saba bananas lining the sugarcane fields

Saba bananas were so plentiful that we often gave them away, left them beside the house for ducks and chickens, or watched farm workers grow tired of eating them steamed.

Today’s prices still shock me.

At the back of our house was a river—used by people to wash laundry, bathe, and where we children played endlessly. It was clean, unpolluted, alive.

That river was also my first art studio.

There was a part of it rich in clay (bak-yas), and I loved molding figures from it. My favorite subjects were human figures, mimicking the images we saw during Holy Week processions—saints, penitents, solemn faces frozen in devotion. For hair, I used the fine moss growing near the riverbanks. It felt logical. Natural. Accurate enough for a child.

Along the banks grew native fig trees (tambuyog), heavy with fruit. We used those fruits as tires for our handmade toy cars, made from sticks and scraps. We were ridiculously creative then—something I sometimes feel children today are quietly missing, no fault of their own.

Wild fruits grew everywhere near the river. One of them was anagas—its fruit looked like a tiny cashew. Before eating it, we would chant:

“Anagas, anagas, baylo ta ngalan—

imo si Jojo, akon si Anagas.”Roughly translated, it meant:

“Anagas, anagas, let us exchange names—

you take Jojo’s name, and I take yours.”

We believed that if we didn’t say this chant, our mouths would swell or rot after eating the fruit. Completely unscientific. Completely convincing.

There were also small, well-built wells along the riverbanks—bubon—which some families used for drinking water. The belief was that the sand had already filtered the water anyway.

And true enough, we didn’t get sick drinking from it.

Before drinking, though, there were rituals.

We would make the sign of the cross on the water, believing it would protect us from stomach problems. Sometimes, we would tie a leaf beside the well, a quiet gesture to honor the unseen elements believed to reside there.

Faith and folklore lived side by side.

Catholic prayers and pre-colonial respect for nature didn’t argue. They coexisted.

We gathered shells: banag, iwis, kohul (ko-ul in Ilonggo)—names that don’t need English because they belonged to a world that didn’t ask to be translated.

My father built a pakusad—a stone-and-bamboo installation positioned across the river, covering its width and serving as a natural fish strainer. During heavy rains, when the river swelled, fish would gather there.

Seeing fish trapped in the pakusad felt like a literal blessing from above.

Of course, I didn’t think of it that way as a child.

I just thought it was… natural.

Buckets of fish.

No drama.

My mother said river fish were malansa—too fishy. She cooked them for us anyway, but never ate them herself. She only ate the ulang—freshwater shrimp, the kind that tasted cleaner, gentler.

Food wasn’t curated.

It wasn’t photographed.

It wasn’t branded.

It was gathered.

Taro Fields, Gata, and Quiet Plenty | Gen X Childhood

What we had was never loud. It didn’t announce itself. It didn’t arrive wrapped or labeled or measured. It was simply there—steady, dependable, and unremarkable in the way only abundance can be when you grow up inside it.

Near the river, my mother had over 500 square meters of taro (abalong), growing almost on its own. We could never finish the supply of leaves. Most of them went to feed our pigs, not because they weren’t useful to us, but because there were just too many.

The stalks—takway—were often given away. I remember an aunt from Bacolod who would leave our place with sacks of them every time she visited. She sold home-cooked food for a living, and for her they were important. For us, they were part of the background—like shade, or water, or time.

The young leaves were different.

Cooked with dried fish, or pork slowly simmered in gata—those were my favorites. We didn’t talk about these meals. We didn’t call them anything special. They appeared on the table, we ate, and the day continued.

Scarcity wasn’t something we talked about.

We had vegetables everywhere—so many that giving them away was normal. That was how farm life worked then. You planted what you could, and you asked from others what you didn’t have. There was no keeping score. No sense of loss. Just movement.

Uncertainty, though, was always there—quiet, constant.

The weather could change. The harvest could fail. Prices could fall. Nothing felt permanent, even when everything seemed full.

Looking back now, I realize how much that combination shaped us—having enough without making a ceremony of it, giving without needing acknowledgment, learning early that abundance could disappear just as quietly as it arrived.

We didn’t call it anything then.

We just lived it.

And perhaps that’s why, years later, certain things still surprise me—the way vegetables are counted carefully, the way food is discussed with urgency, the way abundance is sometimes spoken of as if it needs defending.

I don’t say this with nostalgia.

Just recognition.

Horses, Goats, and the Accidental ( Maybe Destined?) Entrepreneur | Gen X Childhood

By Grade 4, I was already riding horses—bringing food to my father while he monitored the fields.

My older sisters didn’t know how to ride. We (with my siblings) were all trained to ride the horse. It was planned. And those trips to the fields turned out to be more than errands. They became my first taste of enterprise.

Bringing food to my father meant bringing food to the farm staff as well. And somewhere along the way, a very young version of me decided this was a business opportunity.

I started small.

Bread packs bought at ₱1.00, sold at ₱1.25.

Coconut bars—papá (with all the á’s, as we called it).

Sometimes ube bars.

Always a 25% markup.

My father released salaries every Sunday evening, so whatever the farm workers owed me was already deducted from their pay. Clean accounting. No chasing. No awkward conversations.

And yes—believe it or not—as early as elementary school, I was already lending money at 25% interest. (OMG. I know. 😂)

The amounts were modest: ₱10, ₱20, the biggest maybe ₱50. But still. Among all my siblings, I seemed to be the most enterprising. Not necessarily the smartest—just the one always calculating quietly.

That didn’t mean we weren’t trained in everything else.

At home, everyone learned survival skills. Cooking. Cleaning. Fetching water. Cleaning rice—tahúp—because we milled our rice locally, and it arrived with husks and grit still mixed in. Nothing was pre-cleaned. Nothing was automated.

Our parents reminded us constantly:

You should know how to survive.

Oddly, despite all that, I never learned how to ride a carabao—even though we had a couple for farm work. Horses, yes. Carabao, no. Some skills choose you, I suppose. ( or perhaps riding the horse is more Fabulous? OMG hahaha)

In the afternoons, we fetched goats, tying them to patches of grass to graze. No one stole animals. No one needed to. Trust wasn’t something we talked about—it was assumed.

Looking back now, I realize that kind of early autonomy does something subtle. You don’t grow up waiting for praise. You grow up trusting your ability to figure things out.

Psychologists later gave that a name: competence-based confidence—confidence built from doing, not from being applauded. It’s a trait often associated with Gen X, shaped less by affirmation and more by early responsibility (Duckworth et al., Grit).

At the time, though, I didn’t know any of that.

I just knew how to ride a horse, sell a snack, count my change, and bring something useful to the table.

And somehow, that felt normal.

No Internet. Just Memory | Gen X Childhood

We didn’t document our lives.

We remembered them.

We talked. We observed. We internalized.

That’s why many Gen Xers today:

- speak deliberately

- dislike performative emotion

- question trends

- value privacy

- distrust excessive self-promotion

Studies on digital generational behavior show Gen X maintains stronger boundaries between public and private identity than later cohorts (Prensky, Digital Immigrants vs Digital Natives).

So Why These Gen X Traits?

Because we were shaped by:

- economic volatility

- political uncertainty

- environmental abundance

- early responsibility

- limited explanation

- constant adjustment

These aren’t attitudes.

They’re adaptations.

This Is a Series. This Is Just Part 1

This series is really about growing up Gen X—the quiet things that shaped us, the small moments that became lifelong habits, and the values we carry without always realizing where they came from.

In the next parts, I might talk about:

- My elementary school years

- First crushes, first heartbreaks, and love as a Gen X

- Work ethic and career identity

- How farm life shaped my adult values

- Money, risk, and early independence

- Friendship, loyalty, and chosen family

- Discipline, authority, and how we were raised

- Raising younger generations in a very different world

- Aging as Gen X (with humor, of course)

- And yes… maybe even a love story. Char. 😄

If you’re Gen X—or simply curious about our generation—comment below and tell me which topic you want me to write about first.

This is only the beginning.

References

- Strauss & Howe, Generations Theory – Psychology Today

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/our-stories/201811/the-origins-generation-x - Ryan & Deci, Self-Determination Theory

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0191886913001516 - Twenge & Campbell, Generational Value Shifts – APA

https://www.apa.org/pubs/journals/releases/psp-752-4-745.pdf - NIH: Early environmental stress and adaptive behavior

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6207961/

More Stories

- KUALA LUMPUR TOURIST SPOTS

- BEST HOME ACNE REMEDIES

- ILOCOS SUR TOURIST SPOTS | THINGS TO DO

- BIRI ISLAND ROCK FORMATION | SAMAR, PHILIPPINES

- 20 THINGS TO DO IN HANOI , VIETNAM | TOURIST SPOTS

- 23 POPULAR BOHOL TOURIST SPOTS | ATTRACTIONS

- Kristin’s Steakhouse | Ending the Day With Steak

- Ship Shops: Still Floating After 25 Years

- NEPC Holds IEC Activity for Bacolod City Vendors

- Tourism in Negros Occidental: Driving the Provincial Economy

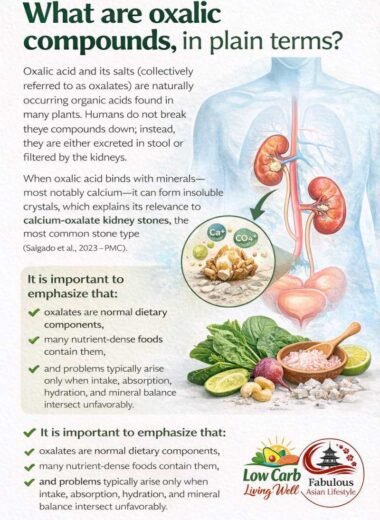

- Oxalic Compounds and Low-Carbohydrate Eating

- Relief to Fire-Affected Families in Barangay 10 | Negros Power

- Aling Lucing Sisig: A Taste of Pampanga’s Iconic Sizzle | A Review